Oldsmobile, Pontiac, Saab, Packard, De Tomaso, Rover, DeSoto, Jensen, Studebaker, AMC…

The list goes on of once famous automakers now defunct, buried in the annals of history.

Yet with Fisker’s situation so painfully public, and with so many automakers and mobility companies suffering similar consequences in the last couple of years, we find ourselves asking whether the current situation is a little too pronounced, or simply a natural part of car-capitalism.

War and Innovation in the Good Ol’ Days

During the founding years of the car industry, let’s say the twenty-five years following Benz’s Patent-Motorwagen, there was all manner of young companies scrapping for a share of what was clearly something huge.

In fact, there are many examples of automakers who had huge impacts on the industry yet no longer exist or, even worse, are essentially forgotten.

There was De Dion Bouton, who we wrote about recently and who by 1900 was the largest automaker in the world. Duryea Motor Wagon Company were established in 1893 and built the first gasoline-powered car in the US, whilst I hope you will at least have heard of the legendary Studebaker, who had existed since 1852 as a carriage maker.

In truth, in Europe and Britain alone there were more than a hundred companies building cars by the turn of the century, never-mind those in the US, Asia, Latin America and Australasia. These were fertile times rife with experimentation, evolution and … consolidation.

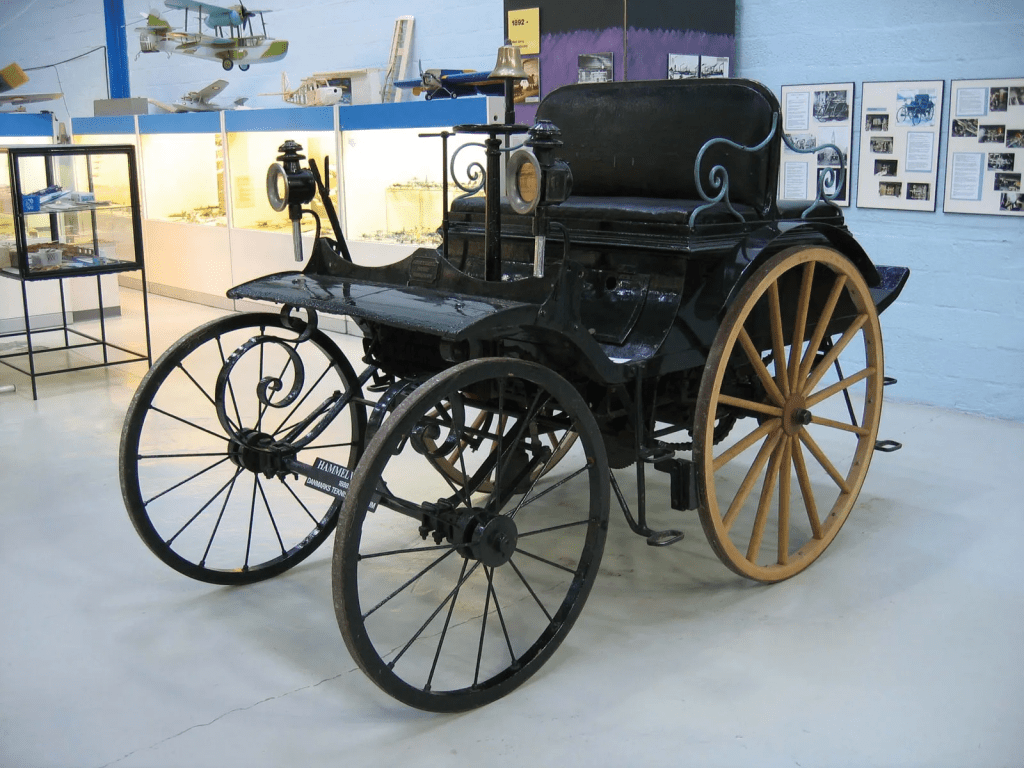

Fact: The oldest running automobile is an 1888 motorcar by a Danish company called Hammel. Yeah, I’d never heard of them either, but it proves the point.

By 1912, there were anywhere between 200 & 300 marques, the initial motorcar’s success having laid the foundations for an industry that felt sustainable and unstoppable.

And then, of course, World War I arrived.

Companies across Europe, from Belgium to Britain, Poland to Portugal, turned their factories, however small, into supporting the war effort, irrespective of whose side they were on. Then it spread globally.

Of course, as is always the case, some manufacturers benefited from the war effort and continued to grow, whilst some didn’t survive and yet more were actually formed in the ashes of the war’s aftermath.

Bentley started life in 1919, for example, taking advantage of available aluminium from war planes to build a mightily successful company who raced to Le Mans glory and created elegant, luxurious GTs and sports cars.

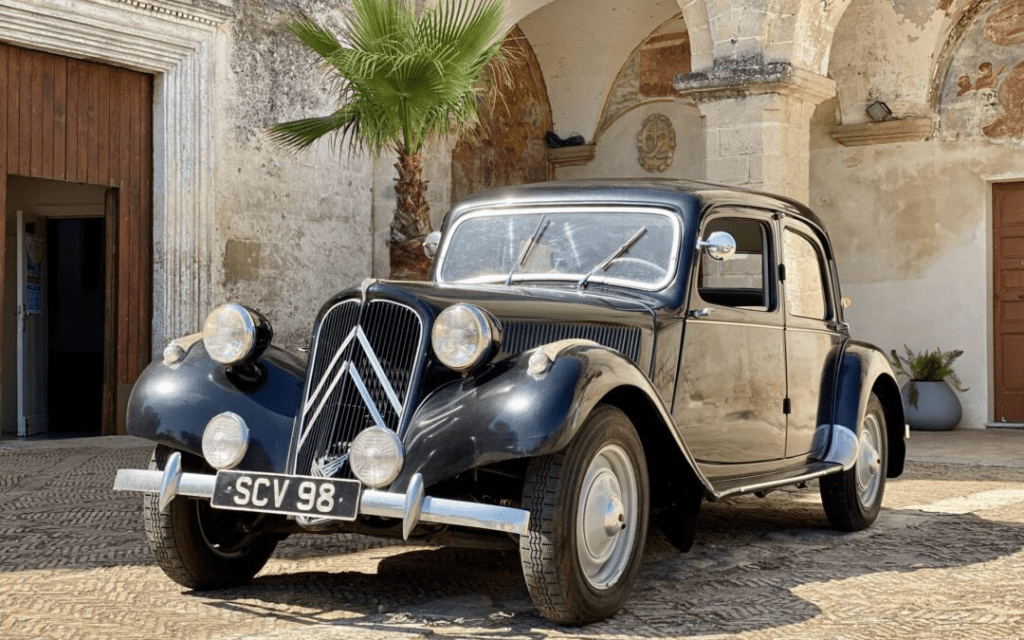

Citroën too began life in 1919 and took advantage of learning from building aircraft, whilst Alfa Romeo truly started as an automotive brand in the years following the conclusion of the war and Mazda, who had originally started life as Toyo Cork Kogyo Co., a cork-maker, in 1920, kicked off car production a few years later.

Crises and Consolidation

The 1920s and ’30s brought all manner of chaos to the world, and the auto industry suffered considerably.

Whilst the early ’20s saw great progress, particularly with the growth of coach-building and the increasing breadth of cars available to a broader range of customers, the Great Depression caused a complete rethink.

Companies like Hispano Suiza, who’s foundations were highly sought after by coach-builders, Isotta Fraschini of Italy, Delage of France and wonderful innovators like Cord, Duesenberg and Pierce-Arrow from North America had all shuttered their factories by 1938.

Or at least stopped making cars.

So the ’20s were a success, right?

Absolutely. Closed bodies (something we certainly take for granted now), four wheel brakes, inflated (balloon) tyres, electric starters, interior standardisation (including the steering wheel and interior layout we know today) and, of course, mass production were all developed during this decade.

So why did this consolidation continue in the ’20s? Were these unions a factor in the technical progress? Though impossible to say, having less competition gave more of the market to a smaller amount of players, giving each in turn more money for R&D and experimentation. So it can’t have hurt.

Yet even more advancement was witnessed during the tough times, a common theme throughout history, and not just automotive.

Strife breeds creativity, from necessity, and it was the ’30s that brought not consolidation but, as we’ve mentioned, the closure off businesses. However, we also have the decade to thank for: the unibody, independent suspension, aerodynamics, front-wheel drive, power steering, four wheel drive, overdrive and hydraulic shock absorbers.

However, three of those came from just a single car, a car that almost bankrupted its maker. It’s also worth remembering that innovation is expensive, unfocussed innovation even more so. Perhaps that’s what caused so much instability during the early decades; it’s expensive to stay on top of your competition.

Whatever the reasons, by the time World War II arrived, the motorcar had changed dramatically, had broadened into something that a majority of people could afford to buy (economic crisis aside) and had begun to reshape how cities – hell, countries – were even designed.

In just 50 years it had changed from a steam-powered quadricycle to a mass-produced home on wheels, something that could reliably carry you thousands of miles in comfort, thanks also to the evolution of public infrastructure.

And all of that happened alongside mass-bankruptcies and the loss of some iconic names. In fact, marques who didn’t exist until after WWI, such as Bentley and Citroën, still found time to go bankrupt before the second one began!

Despair…

For many automakers, surviving the war had been one thing, but trying to pick yourself up, dust yourself down and go again, in an impoverished world with obliterated public infrastructure, was too much for many, and further bankruptcies and collapses followed.

REO Motor Car Company, who produced some wonderful automobiles for the American market, ceased car production in 1954, a combination of changing tastes and the growth of the US “Big Three”.

In fact, 1954 also witnessed the consolidation of Packard with Studebaker, and the legendary Nash Motors with Hudson Motor Car Company.

It’s also forgotten that, following WWII’s negotiations and an apparent Allied desire to suppress any remaining pro-Hitler sentiment, the allowed output of German OEMs was severely limited for several years.

BMW were on the brink of bankruptcy until the Neue Klasse of vehicles saved the brand in 1960, whilst Porsche suffered immensely in the late ’40s with Ferdinand having been arrested, though not tried, for war crimes.

In Japan, Toyota, then in its infancy, was rescued from bankruptcy in 1949, suffering from the combination of fluctuating inflation and an impoverished public. Mitsubishi, thanks to their experience making trucks, scraped by.

The late ’50s also saw the collapse and consolidation of the coach-building industry, with the most successful creators predominantly based in mainland Europe.

With companies like GM showing the power of in-house design teams – though not everyone was fortunate enough to find a Harvey Earl – and many OEMs turning their attention to simple, low-cost utilitarian offerings in a war-torn world, coach-building didn’t seem practical.

There are a boatload of coach builders who subsequently disappeared, and we cover them in a separate CLT series starting here, but legends such as Carrozzeria Touring, Saoutchik, Van den Plas and Figoni et Falaschi all ceased operations before the end of the ’50s.

This is getting depressing, isn’t it?

And Hope!

But hope is not lost, for this unstable period also brought wonderful innovation, and even the birth, and re-birth, of some iconic brands.

Honda didn’t exist until 1946. A company who in 2023 sold 3.7 million automobiles alone, never mind all of the other stuff. Volkswagen (if you’ve heard of them) were founded by Hitler and of course only progressed post-WWII.

For goodness sake the original Scuderia Ferrari was absorbed into Alfa Romeo in 1937 before Enzo, having left Alfa due to disagreements, founded his own company, then supported Italy’s war efforts and used the money from the lucrative contracts to truly kickstart the famous marque in 1947.

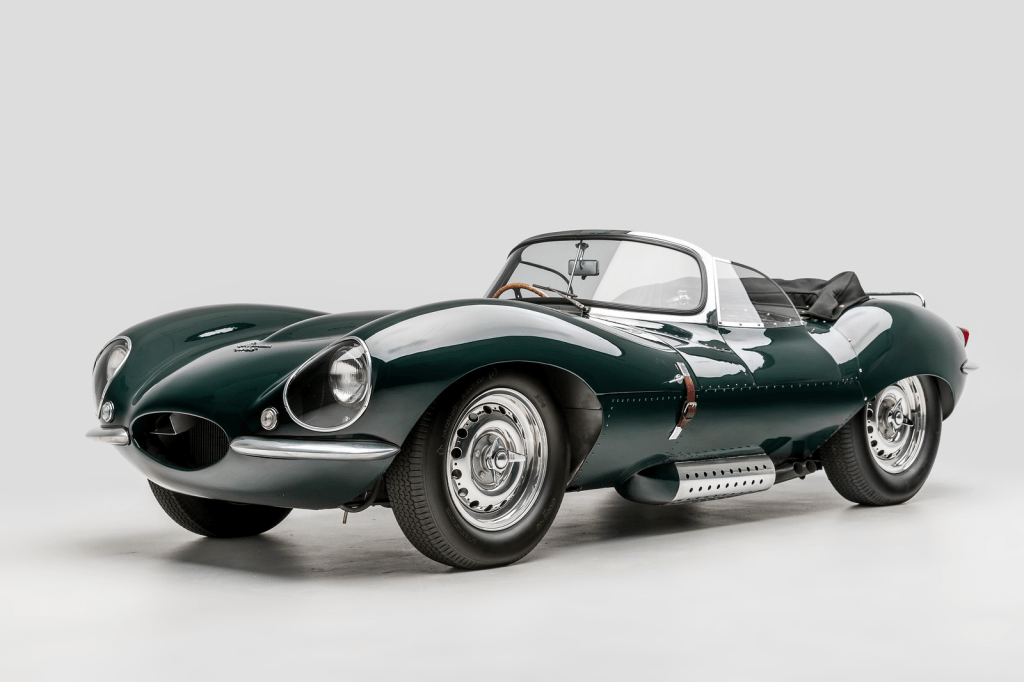

You can add Jaguar to the list, who only became Jaguar cars in 1945, and who’s racing success only arrived in the ’50s and ’60s.

It was the same for Aston Martin, who had faced several financial challenges in the pre-WWII years, but whose fortunes were transformed by new ownership in 1947.

Land Rover didn’t exist until 1948, Lamborghini until the ’60s, and we’ve already mentioned the fortunes of Porsche. And beyond just the success of companies, the cars being created in the late ’40s and ’50s are absolute wonders, whether road or track-based.

Swinging and Axing

Though the ’60s saw a relatively calm period, at least within the automotive industry, there were still some brands that ceased to exist, including the always-innovative Studebaker, Austin Healey of Sprite fame, Facel Vega, Hudson Motor Car Company and the experimental NSU from Germany.

The relative stability, for once, brought wonderful innovation, especially with the growth in concept cars whose popularity had been pushed by Harvey Earl of GM.

Car racing was at fever-pitch, albeit embroiled in a race to improve safety, there was vast consolidation of brands across the world and cars of all types, from classic microcars and small family cars to stunning GTs and true race cars were being created.

Then the ’70s hit.

If the ’60s was a filter for extravagance, or at least removing automakers who’s portfolio didn’t reach beyond niche, the ’70s was a brutal attempt to get rid of anyone but the most determined survivors. Sort of like the Hunger Games, but for cars.

Lamborghini struggled to sell their V12 cars during a period where oil prices were skyrocketing and not even the wealthy had bundles of spare cash. De Tomaso faced the same feat, but survived by the skin of their teeth.

Chrysler, a “Big Three” automaker, needed a government bailout to save them in 1979, whilst on both sides of the Atlantic, AMC and British Leyland – similarly awkward conglomerates of misfit automakers – either divested assets and disappeared or ceased to exist.

Saab, a company close to the hearts of many car fans, suffered financial challenges in the ’70s from which they never full recovered, whilst the awkward stories of Maserati and Lancia are widely publicised.

Though Maserati survives today, and is being well-financed by Stellantis, we’re yet to see whether the same can be said for the iconic Lancia marque.

So, if the ’60s were easy, and provided wonderful car creations, and if the ’70s caused such turmoil as to wheat out all the remaining automotive chaff, turning every brand into a lean, mean, combustion-powered machine, then surely the ’80s would prove to be remarkable… right?!

The ’80s

Well the world didn’t get much respite in the ’80s, so neither did the car industry.

Bookmarked between the first Persian Gulf war in September 1980 and the fall of the Berlin Wall (and the gradual erosion of the USSR) in November 1989, there was an awful lot that happened in between that influenced the industry.

For starters, automakers such as Talbot, AMC and Jensen, who were hanging on for dear life in the ’70s, finally said goodbye in the ’80s.

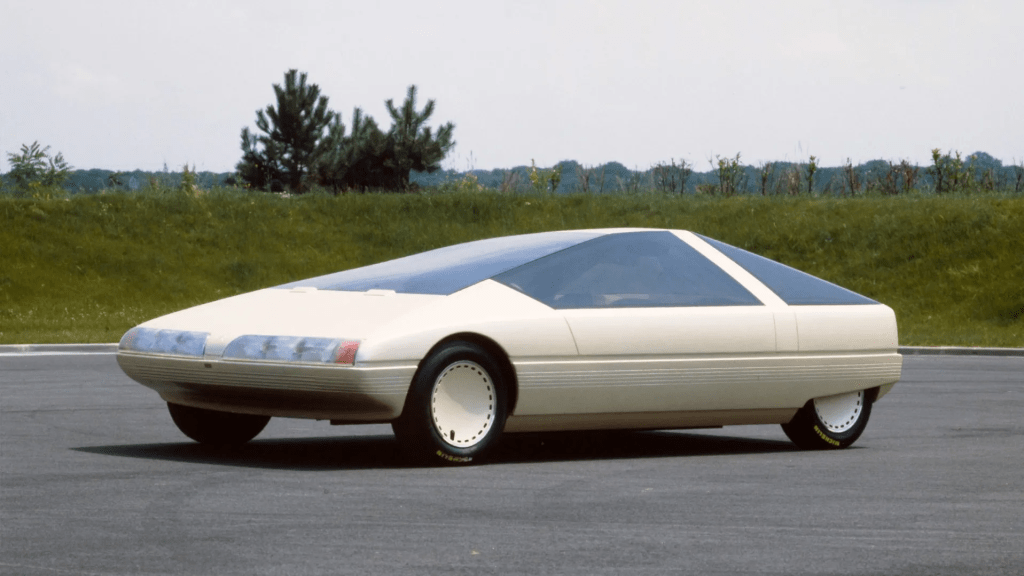

A decade when nearly every family, at least in the USA, had a television, and with the birth of modern electronics, which allowed people to have mobile telephones, portable CD players and VCRs for the first time, these inventions impacted what people expected from their cars.

The ’80s saw all manner of whacky concepts trying to interpret how digital technology would be used in the modern motorcar, whilst new safety standards also created all manner of weird and wonderful interpretations.

This evolution led to the eventual end of the iconic Checker Cab Manufacturing Company in 1982, famous for the yellow taxi cabs in cities like Manhattan, and despite DeLorean’s wild ambitions, they too ceased to exist from 1982.

Once again, the auto industry, faced with rapidly changing consumer trends, economic challenges and infrastructure restrictions, was forced into further consolidation, a filtering of the waste and a need to continue innovating.

So that’s exactly what it did.

Consortiums sought new financing, difficult-to-position brands were discarded and funds allocated to focussed innovation that had at least a slim chance of impacting future vehicles. Though not always.

It wasn’t a perfect system but the industry, now 100 years old, had adapted to everything that had been thrown at it thus far; it wasn’t going to give in now.

Complacency and Carelessness

If the ’70s were chaotic, and the ’80s brought crazy concepts and technical challenges, the ’90s were reserved almost solely for complacency.

Of course you’ll find some examples of wonderful products in amongst the mess, such as the Honda NSX, Nissan Skyline R32, the Toyota Supra or the BMW E36 M3. Interesting that the majority of these originated from Japan…

It was a time of economic calm and, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Persian Gulf War in 1991, a relatively peaceful time. Oil prices steadied, governments had money in their pockets and so did the consumer.

This led to automakers pushing boundaries far less than they’d ever done, safe in the knowledge that their products would be bought anyway. Cars like the 1994 Ford Scorpio, the 1995 Fiat Bravo and the Peugeot 406 stand out for all the wrong reasons. As does the shocking Pontiac Aztec which was developed in the late ’90s before being released in early 2000.

This complacency, and an apparent lack of financial restraint, led to several huge automakers also suffering financially.

In 1992 GM was forced into huge cost-cutting measures due to a ballooning balance sheet and massive inefficiencies as it battled to integrate recent additions to it’s stable, the same problems Fiat suffered, alongside declining revenues and model popularity.

Ford, Renault and Chrysler all suffered too, as did Mitsubishi, who for a while disappeared in all but a few minor markets, only appearing very recently with the uniquely positioned Outlander PHEV, to its credit.

By the turn of the century, and with cost-cutting measure in place, it was time for the huge automotive conglomerates to begin slashing nameplates from their stables.

Daewoo, Oldsmobile, Saturn – a failed new marque that only emphasised GM’s complacency – were all discarded, whilst Plymouth, Hummer, Mercury and Pontiac all disappeared too during the first decade of the new millennium.

Isuzu returned to it’s foundations, and heavy trucks, a tragic decision for anyone who appreciates the off-road capability and durability of their Trooper nameplate.

And Yugo, a legendary soviet marque who dominated car sales in the former Yugoslavia also disappeared into the ether, never to return.

By the end of the sub-prime mortgage financial crisis that appeared from nowhere and gripped the whole world, it was pretty much 2011 and the automotive industry was moving into a whole new world of change.

But the trail of carnage left behind made many question whether it had been worth it.

Transitions

Since the beginning of 2011, it’s safe to say that the world is almost entirely different from when the motorcar first surfaced in the mid-1880s, yet some things remain very similar.

For starters, though the EV transition has stumbled in the last 18 months, the fundamental propulsion system for cars is changing drastically, whether powered electrically, via batteries, liquid hydrogen or something entirely different.

This also brings the challenge of public infrastructure, the precise challenge faced in the founding years when public roads didn’t really exist, nor did fuel stations. Cities looked very different.

As such, there have been many new companies coming to the fore, all keen to position themselves for a piece of the ever-growing pie. Sound familiar?

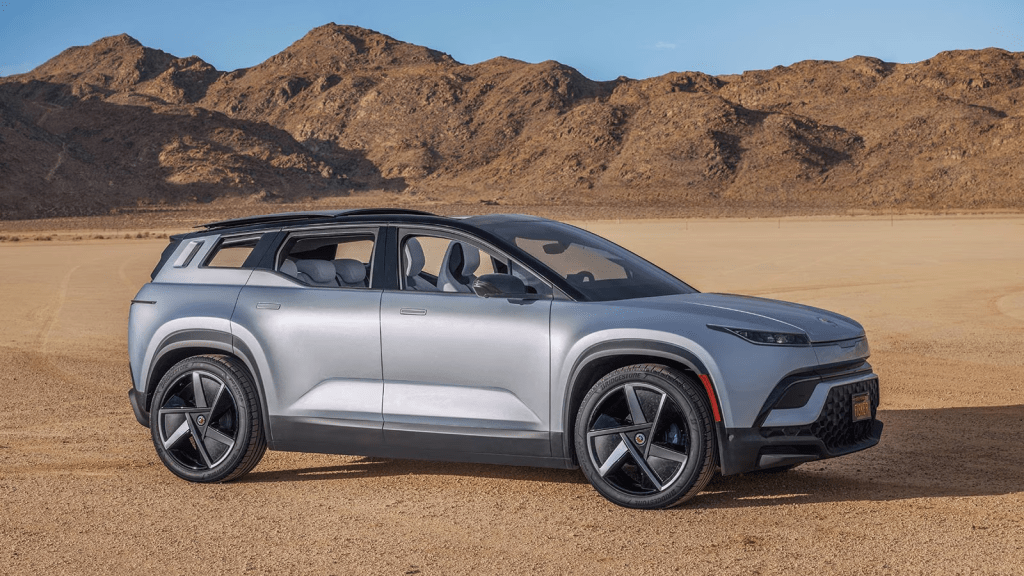

Exactly. We’re not yet in a position where consolidation becomes the norm, but if Fisker find themselves selling portions of the company to an OEM such as Nissan, as has been widely speculated, or Rivian require further financial input from someone such as Amazon, things may get interesting.

Starting a car company from scratch is incredibly expensive, especially nowadays. Long gone are the days when companies such as Lotus, as we discussed recently, can simply start off in a garage and begin making cars.

So what’s next? Well, expect further bankruptcies.

As we’ve learned, this seems to be part and parcel of this dynamic industry we love so much.

New companies arrive with a different way of thinking. If they succeed, like Tesla for example, they can disrupt the whole industry and force a rethink. If not, they either get absorbed by a large OEM and change things from within, or they’re shown to be nothing more than a flash in the plan, ashes that create fertile ground for the next big change.

Either way, don’t expect much to change, except the constant that is change itself.

***

This article became much bigger than originally planned, but we hope you enjoyed it all the same.

After all, it’s important to cover the complexities of this industry we love so much, so as to get a bigger picture.

And don’t expect the content to stop, we have so much more to give! So subscribe below to avoid missing out 🙂

Leave a comment