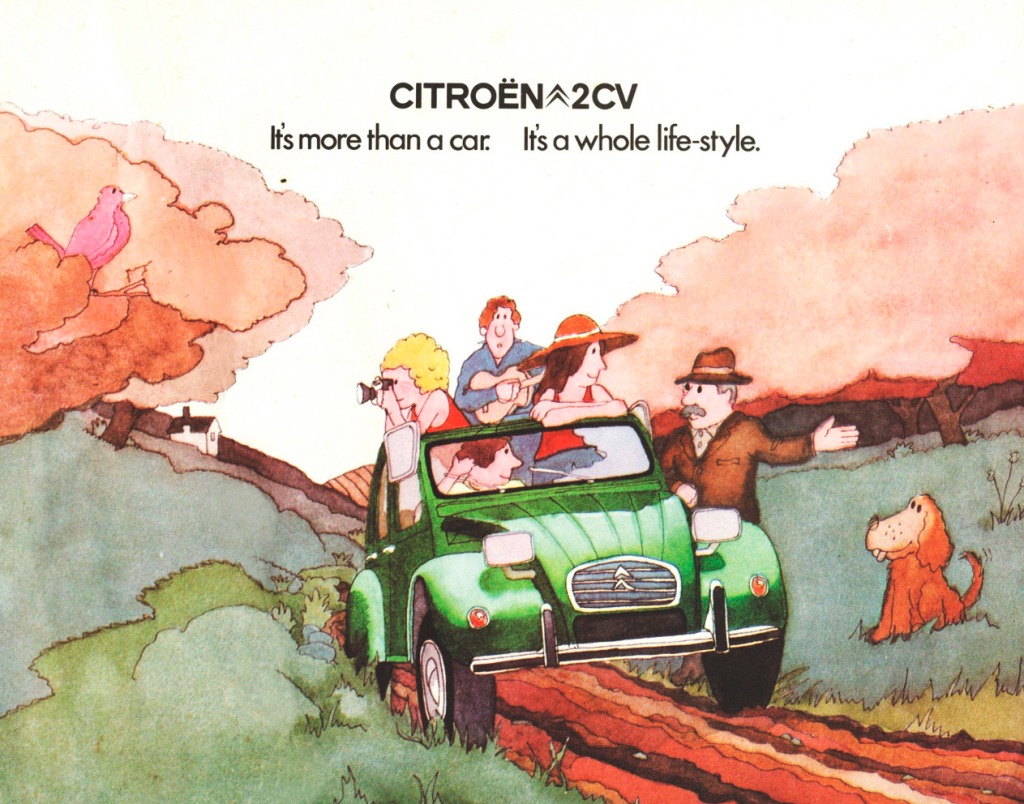

You’re driving through the Loire valley, rolling fields filled with crisp vines of grapes abound either side of the small dusty road. The spring sun shines high in the sky as you wind your way towards another cute village. You stop at the roadside and, under the shade of a wild apple tree, reach into the trunk and pull out a picnic basket chocked full of local cheese, wine, fresh bread and confitures. And what’s the car you’re driving? My money is on a Citroën 2CV. The quintessentially French, timeless classic that’s now more popular than ever. But it almost didn’t exist; here’s the marvelous story.

The year is 1934, a year I’m sure is etched deeply into your memory. France is in the midst of the Great Depression and in most economies of the developed world, it’s not the best time. Citroën, a pioneering French car manufacturer, who had been supporting the armament manufacture business during the first World War because, well, they had no choice, were back in business with their Traction Avant model. It was the first car to be built as a unitary frame and body, and pioneered both four wheel independent suspension and front-wheel drive; features we still see today. In fact, it was so innovative that it bankrupted the company. Thankfully, the kind people at Michelin, the tyre company who also “star” restaurants, stepped in and rescued Citroën. Whether it was French nationalism, an awfully kind gesture or a strategic commercial decision, Michelin saw opportunity. And they placed their own Pierre-Jules Boulanger as Head of Engineering – this is important later.

So now we have a highly innovative company, bankrupted by their own ambition and a financial crisis, rescued by another highly innovative company determined to keep the vision of Citroën alive. You have a nation, heavily reliant on agriculture with a majority of the population still using horse and carts, unable to afford a motor vehicle. And you have a market saturated by luxury vehicles becoming expensive and technically complex. Cue the 2CV, à la back to basics French minimalism.

The race to squeeze more technology and luxury into a vehicle is as old as the motor vehicle itself, so when Boulanger proposed the exact opposite direction, it raised some questions. But there’s sound logic here – since his first days in office as Head of Engineering, he had envisioned a car for the many, a car for low income families across France and the rest of Europe. He had even written a specification for it: To make a car that can carry four people and 50kg of potatoes or a keg, at a maximum speed of 60 km/h, with a consumption of 3 litres per hundred kilometres and low maintenance costs. Interestingly, a vehicle concept similarly envisioned by both Hitler and Mussolini.

The 2CV, envisioned as a way of getting rural populations away from the horse and cart and into a simple, low cost and efficient motor vehicle, progressed rapidly in secret. By 1939 the prototypes were ready, all 49 of them. By the 28th of August, an initial run of 250 production vehicles had received approval for the French market. Boulanger’s vision was about to take shape. Then, less than a week later, France declared war on Germany and World War II kicked into gear. Bugger.

French factories once again switched into hyperspeed to support the war effort, and all other product development was put on the back-burner. Except that wasn’t quite the case. Even when Germany countered the French and took over the country, the 2CV development continued behind closed doors, expressly against the wishes of the Nazi regime. Mr. Hitler and Co. wanted every ounce of energy focussed on supporting the German war machine, which was looking west towards Britain and east towards Russia. It didn’t go down well when Boulanger not only refused to meet face-to-face with Dr. Ferdinand Porsche (of the eponymous company and VW Beetle fame) and the rest of the German high ranking officials, but actively told Citroën’s factory to “go-slow” on the Wehrmacht truck manufacturing line. He encouraged the workers to sabotage the oil dipsticks by putting notches in the wrong places causing vast amounts of trucks to suffer from engine seizures. This labeled Boulanger as an enemy of the Reich and put him at the top of the Nazi blacklist. What a cool cat.

When France was freed from its slave-like occupation in 1944, priorities shifted. Thanks to the economic damage inflicted on Europe, the market for a vehicle of Boulanger’s vision was stronger than ever. Citroën became increasingly determined for the 2CV to see the light of day. But first, they needed to resolve some key design challenges. A complete redesign of the two-cylinder engine was the first step; all the prototypes had been scattered around Europe in various rail-carts to avoid falling into Nazi hands. And even more challenging, the body panels needed a complete re-design in steel. Designed in a pre-war world, where magnesium and aluminum were in abundance, the entire body had to be re-engineered. Here’s what the to-do list looked like: flat, corrugated body panels to increase strength without weight, a canvas roof that opened the full length of the vehicle, a single taillight, a speedometer attached to the a-pillar and a windscreen wiper motor that varied speed directly based on how quickly the vehicle was traveling. And it was only available in grey. Yummy.

The 2CV (deux chevaux – two horses), wrongly perceived as being the horsepower output of the vehicle, but in actuality is the original tax classification for the vehicle, was officially launched at the1948 Paris Auto Show. At a time when most vehicles were looking to take a leaf out of the books of GM, Ford and other American manufacturers who were cramming more technology and luxury into their vehicles, Citroën had effectively moved in the opposite direction causing widespread criticism from the press. But the people loved it, and order books were overflowing with new customers. With the cost being half that of a VW Beetle, the waiting list soon rocketed from three years to five. People began to pay more for a second hand 2CV than a new one to avoid waiting. By 1951 production reached 100 cars per week and the driver’s door was now lockable, amazing. A panel van, the 2CV Fourgonnette, followed the same year and by 1952, production was up to 21,000 per year.

By 1956, more comfortable and decorative features were added including a large rear window, a large synthetic soft top, and interior trims with striped cloth seats. Ten years after its appearance, the 2CV had a different look: a blue glacier colour and a new dashboard. And that was far from the end of the 2CV’s progression, although it would always favour evolution over revolution.

The year 1960 brought a 4×4 version called the Sahara, which had an additional engine and transmission mounted inversely to drive the rear wheels. Five years later, the 2CV saw the doors switch from “suicide” to front hinged, and the range of colours continued to increase until 1967, when a completely new model was launched as an upmarket version of the 2CV, the Dyane. But whilst the Dyane ceased production in 1983, the 2CV continued in production all the way to 1990. That’s 42 years of non-stop simplistic French beauty.

The 2CV was produced in France, Belgium, UK, Yugoslavia (modern day Slovenia), Ivory Coast, Vietnam, Greece, Chile, Argentina, Spain, and Portugal, where the final 2CVs were made. It was a vehicle desired by the military for it’s ruggedness and low weight; it could be lifted by helicopter into difficult terrain. It won rallies, traversed across the unrelenting landscapes of Australia and Africa and inspired a vast assortment of remakes and interpretations that are increasingly sought after to this day. It even starred in a James Bond film. And yet it continues to set a benchmark for simplicity, efficiency, and single-mindedness as a piece of product design, not just a motor vehicle, more than 70 years after it’s launch and 85 years after its initial conception. If that’s not timeless, I don’t know what is.

Thanks to:

- https://silodrome.com/Citroën-2cv-history/

- https://www.Citroën.co.uk/about-Citroën/our-brand/Citroën-2cv

- http://www.just-auto.com/factsheet.aspx?ID=201

- Reynolds, John (2005). The Citroën 2CV. Haynes. ISBN 978-1-84425-207-7.

- Bellu (2000), p. 250

- Odin, L.C. World in Motion 1939, The whole of the year’s automobile production. Belvedere Publishing, 2015. ASIN: B00ZLN91ZG.

- Reynolds, John (2006). The Classic Citroëns 1935–1975. McFarland & Company, Inc, Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7864-2171-8.

Leave a comment