We all have cars we love. And actually, cars we hate. But it’s a certainty that we know both the name of the car and the name of the brand: the McLaren F1, the Ferrari Enzo, the Lancia Stratos, the Porsche 911, the BMW M3. The list is, almost literally, endless. Yet so often, the people behind these wonderful creations are forgotten, unknown.

Our new series, People of Influence, seeks to recognise the people behind the cars you love. Whether it’s the designers whose vision became a physical reality or the engineers behind the mechanical ingenuity. And where better to begin than the man behind the Morris Minor and the legendary Mini.

Uncertain Beginnings

The year is 1906, the Ottoman empire is clinging to its existence, and in a small port town called Smyrna, now known as Izmir, in Turkey, a baby is born to a Bavarian mother and a Greek father with British citizenship. He would be named Alec. Alec Issigonis.

But the story begins even further back, with a man named Demosthenis, Alec’s grandfather, who emigrated from Greece to Asia-Minor in the 1830s and worked for the Smyrna-Aydın Railway. At the time, the railway was built and run by private British companies, and through his work for them, he gained British citizenship for himself and his family.

This proved to be both a blessing and a curse for the family, when in 1922 Alec and his family, as British subjects, were evacuated to Malta by the British Royal Marines as the Greco-Turkish war came to a head, narrowly avoiding the Great Fire of Smyrna and the Turkish capture of the city.

Personal Difficulties

His father, who was a successful and wealthy shipbuilding engineer, and a big influence on young Alec, would die the same year. And shortly afterwards, in 1923, he and his mother moved to the UK, where Alec would study engineering at Battersea Polytechnic in London. And fail his mathematics exams three times before moving to the University of London External Programme to complete his university education. Persistence.

Despite once describing pure mathematics as ‘the enemy of every creative genius’, he excelled at mechanical drawing and, after completing his education in 1928, he found his way into the design office of a London-based engineering firm called Gillett, where he “cut his teeth” and gained invaluable industrial experience that would shape his future considerably.

Automotive Foundations

He had never before shown a passion for racing and speed, perhaps in part due to the lack of options growing up in the heart of the Ottoman Empire, yet he soon found himself taking part in building and racing cars, competing with a supercharged “Ulster” Austin Seven. By 1934, he was working for Humber Ltd. in Coventry, a manufacturer of bicycles and motorcycles who, by the time Issigonis joined, were focused almost solely on designing and building motorcars. His path was set.

With his growing knowledge and experience of race cars, and his continued work with Humber, he soon designed and built his own front axle for his Austin Seven, which caught the attention of the car’s manufacturer. He went on to make many changes to his Seven whilst at Austin, turning it into a considerably lighter (the whole vehicle weighed only 587 lb / 266kg ) and more dynamic offering. In fact, even after moving to Morris Motors Ltd. in 1936, Austin continued to supply him with engines and he continued to dominate races, both in the 750cc class and even the 1100cc class. His reputation in the design offices and racetracks of Britain was growing rapidly.

The Pesky Mosquito

With WWII looming ominously, he completed his first piece of work for Morris, an independent front suspension system for the Morris Ten that wouldn’t be seen until after the war, on the MG Y-Type. It proved too expensive for the budget Morris, but there was no doubting its technical execution and ability to deliver exquisite handling; it was subsequently used on a host of MGs and other more premium vehicles within the Morris stable. And better was yet to come, when he was given the responsibility for project Mosquito.

Despite his young age, Issigonis was made responsible for the whole design of the Morris Eight replacement, having impressed the chief engineer, Vic Oaks, with his impressive suspension and steering systems designs, but also his views on the automotive future and his general car design work. The project seemed risky at best: all Morris’s funds were tied up with the war effort, civilian car production was banned and the young Issigonis was tasked with designing it all, from scratch, in secret. It was a brave move by both Oaks and Morris Motors’ vice chairman, Miles Thomas, that they would not regret.

From the beginning, Issigonis wanted to produce a practical, economical and affordable car for the general public who would “take pleasure in owning, rather than feeling of it as something he’d been sentenced to”. He wanted the Mosquito to have the design quality of a more expensive car and so designed it from the beginning with a simple, ergonomic approach that is so often overlooked: “people who drive small cars are the same size as those who drive large cars and they should not be expected to put up with claustrophobic interiors”. Simple, huh?!

The Mosquito would be comfortable and spacious but also, thanks to his knowledge and experience of suspension systems, have class-leading dynamics, excellent road-holding and accurate, quick steering, not with the aim of being a sports car, rather something that was safe and easy to drive for everyone.

Avant-Garde

When Issigonis first put pen to paper, with WWII in full swing, he began with the Citroën Traction Avant of 1934, a car widely recognised as pioneering mass-production use of front-wheel drive, four-wheel independent suspension, crash resistant, unitary monocoque body construction and rack and pinion steering. If you didn’t know this, then keep an eye out for a separate article covering the Traction Avant soon!

As was typical of car design and development at the time, the underbody came first, and the design, or style, came afterwards. So he started with torsion bars on each wheel, added rack & pinion steering, then set about maximising the interior space and excellent ride and handling, all within the cost targets of an affordable people’s car post-WWII. Easy-peasy.

Then he shrunk the wheels down to 14”, the smallest of any production car of the time, and shoved them to the far corners of the floorpan; just these two changes were simple measures that reduced intrusion into the cabin space and minimised the car’s unsprung mass, giving better ride comfort and stability. And because of the independent suspension, there was no front axle, which enabled the engine to be pushed low and far-forward, away from the cabin bulkhead. This helped to maximise the cabin space, but also gave the Mosquito nose-heavy steering when only the driver was onboard, providing superior directional stability, but nearly equal weight balance when fully-loaded, so handling and grip remained superior regardless of the load carried.

He also proposed a new flat-four engine in both 800cc and 1100cc guise, with only the cylinders being different between the two. This would also have improved ride, handling and cabin space.

Cold, Hard Reality

But as the war came to a close, the project very quickly went from being a study to a necessity with every automaker scrambling into action. Morris were in dire need of new vehicles, the Mosquito project quickly losing its secrecy as engineers, designers and board members joined the team in quick succession

Many of the board were nervous about the radical proposals of the young Issigonis, despite having the backing of both Thomas and Oak. They ummed, aahed and ripped up several different proposals and combinations of Alec’s ideas, before finally settling on one that included all but the new engine proposal.

Lord Nuffield himself, Morris Motor’s owner, took an awful lot of persuading, famously stating that the early prototypes resembled poached eggs. Issigonis was a fan of American car design, particularly the bulbous proportions of the Packard Clipper and Buick Super, so had used those as inspiration for the exterior design, particularly the sculpted fenders and low front headlamps.

And things got worse when the board insisted on launching the Mosquito at the first post-war British Motor Show in October 1948. A host of Issigonis’ ideas were again reviewed, deleted and reinstalled before an agreement was eventually made.

Early prototypes were seen as too ugly and a last minute call was made to widen them a full four inches, meaning several changes to early production vehicles: bumpers, which had already been made, were cut in half and a four-inch plate bolted between the joint, the bonnet had a flat fillet section added to its centreline and the floorpan had two separate two-inch sections added either side of the transmission tunnel. And then they decided to change the name.

Minor Greatness

The Morris Minor, when it was shown to the public in October, 1948, was an instant success. Despite the nervousness of Morris’ board, it very quickly gained a cult following, both at home and abroad, for its quirky design, unrivalled practicality and a near-perfect ride, unmatched in its segment.

The first series lasted for five years, and more than a quarter of a million were produced in three different bodystyles. Issigonis’ vision and the decisions he’d made had been completely validated.

Four years into its lifecycle, in 1952, he left for Alvis cars, just as Morris merged with Austin to create BMC, the British Motor Corporation. He worked with Alvis for three years before being recruited by BMC to design and develop a three-car family that included the XC/9003, a small town car.

Most of his time was spent on the two larger vehicles, dedicating his time to the understructure, maximising interior space and, as always, pushing the boundaries of the suspension and handling systems. Then the Suez Crisis hit.

Mini Success

All priorities shifted towards the small town car due to fuel rationing and rising prices that meant customers just weren’t interested in large, fuel guzzling vehicles. And just a few months later, in early 1957, prototypes were running and testing some of Issigonis’ mechanical ideas. He had always been most excited about the technical challenges of the small city car, despite having been ordered to focus on the other, larger, vehicles. So he was well and truly in his element when the project became official under the codename ADO15.

The guidelines from the head of BMC were quite straightforward, but certainly challenging: the car should be contained within a box measuring 10×4×4 feet (3.0×1.2×1.2 m); and the passenger accommodation should occupy 6 feet (1.8 m) of the 10-foot (3.0 m) length; and the engine, for reasons of cost, should be an existing unit. That was it.

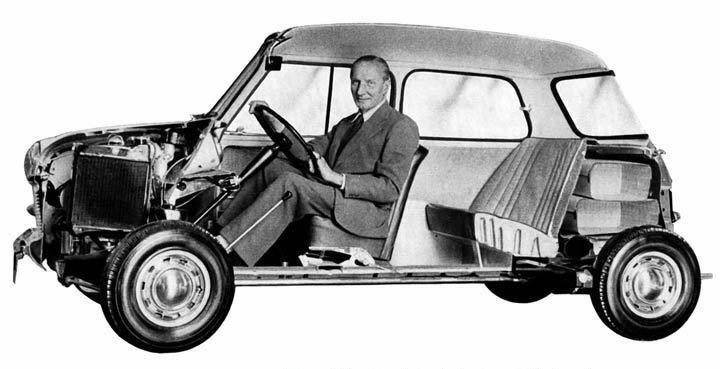

So the first thing Issigonis did was push the four wheels to the corners of the floorpan, much like with the Minor before. Then he took BMC’s A-Series, four-cylinder, water-cooled engine and mounted it transversely in the engine bay, placing the engine-oil lubricated gearbox in the sump, to save space, and designed the front subframe and drivetrain for front-wheel drive. This configuration of transversely-mounted engine and front-wheel drive would come to blueprint the small car segment from then on, unbeknownst to Issigonis and his team.

The suspension itself was designed by Issigonis’ colleague, with his guidance, and used clever rubber cone suspension that gave the Mini go-kart-esque handling, especially when combined with its wheelbase, wheel-positions and overall proportions. It had a top speed of 75mph, despite considerable power and torque reductions to the engine, meaning the Mini was very quick for such an economy car. And by the time customers got their hands on the very first production models, it was already famous and gaining world-wide adoration by the day.

Issigonis had done it again.

Lasting Legacy

Whilst the Morris Minor remained in production for 23 years, totalling more than 1.6 million vehicles, Mini production lasted 41 years and well over five million were built and sold internationally.

Both of Issigonis’ creations took inspiration from other vehicles, but their execution was original, distinctive, and they became blueprints for their segments, solving problems that had existed for many years. Both the Minor and Mini are used as templates even today and are highly sought after by collectors and car fans all around the world.

Issigonis himself was appointed Technical Director of BMC in 1961 and would hold the role for ten years, overseeing vehicles such as the Morris 1100, Austin 1800 and the Austin Maxi. The ‘60s were a difficult time for the British car industry and saw extreme cost-cutting measures made throughout the decade, before political intervention at the end of the ‘60s brought many manufacturers together under the British Leyland brand.

Whilst some people criticised Issigonis for creating cars that caused repair and maintenance costs to spiral, BMC’s number one concern during the ‘60s, his contemporaries named him “the Greek god”, and when he left his post in 1969 to become “Special Developments Director”, his time had come. He left British Leyland two years later, in 1971, but continued to work on his own projects until his death in 1988.

What’s abundantly clear is that Alec Issigonis was someone who always strived for more, who always pushed technical boundaries in order to improve the lives of those buying the products he designed. We often talk about James Dyson and Steve Jobs when we refer to pioneers of iconic, desirable products, yet Alec Issigonis created two such products that lasted well over twenty years and hardly changed during their entire lifetime. Not only that, but they set a template that, 60+ years on, is still being used, and the cars he created not only still exist, they’re more desirable now than ever before. If that’s not a legacy, then I’ve no idea what is.

***

If you enjoyed this article, the subscribe to CLT so that you’ll be the first to know when we next publish the articles that you love so dearly.

Leave a comment