You may have already gathered from the articles I’ve written that I love quirky cars.

Of course, I will argue that the quirks I love aren’t quirks at all, rather well-conceived, customer-led features, capabilities and designs that make vehicles not just lovable, but lovable to the point of obtaining cult status.

And I would argue that there’s one brand who’s created more of these vehicles than any other: Citroën.

Not that you’d guess that from the gravel they churn out now. So what the hell happened?!

Filling the Gaps

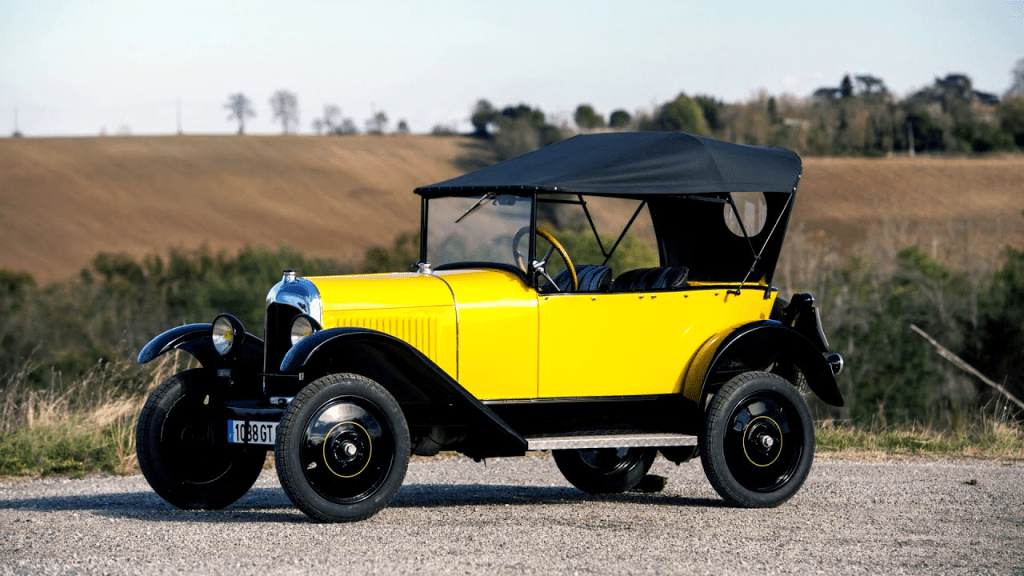

Despite Andre Citroën and a few engineers working with the car manufacturer Mors pre-WWI, and with their factory in full use during the war producing armaments, it’s fair to say that Citroën’s experience designing and creating motor cars was limited.

But with WWI in its final moments, Mr. Citroën looked into the future, imagined peace and prosperity… and his factory dormant and unproductive. That’s when he had the idea for a car brand.

Within an environment where Renault and Peugeot, in France alone, were well-respected brands with immaculate experience, the marque went on a hiring and product development rampage. What they lacked in experience they made up for in confidence and gusto.

Beyond product development, Citroën even had the Charles de Gaulles to use the Eiffel Tower in Paris as the world’s largest billboard for their ventures, something recognised by the Guinness Book of World Records.

They helped convert vehicles with Kégresse tracks (rubberised belt tracks) and used them in sponsored expeditions in remote locations around the world, supporting the medical and scientific communities.

They believed in doing things a little differently, and their confidence knew no bounds.

The marque encouraged and supported tests that pushed their vehicles to the limits, with a Citroën 5CV Type C Torpedo being the first motor vehicle to travel the circumference of Australia.

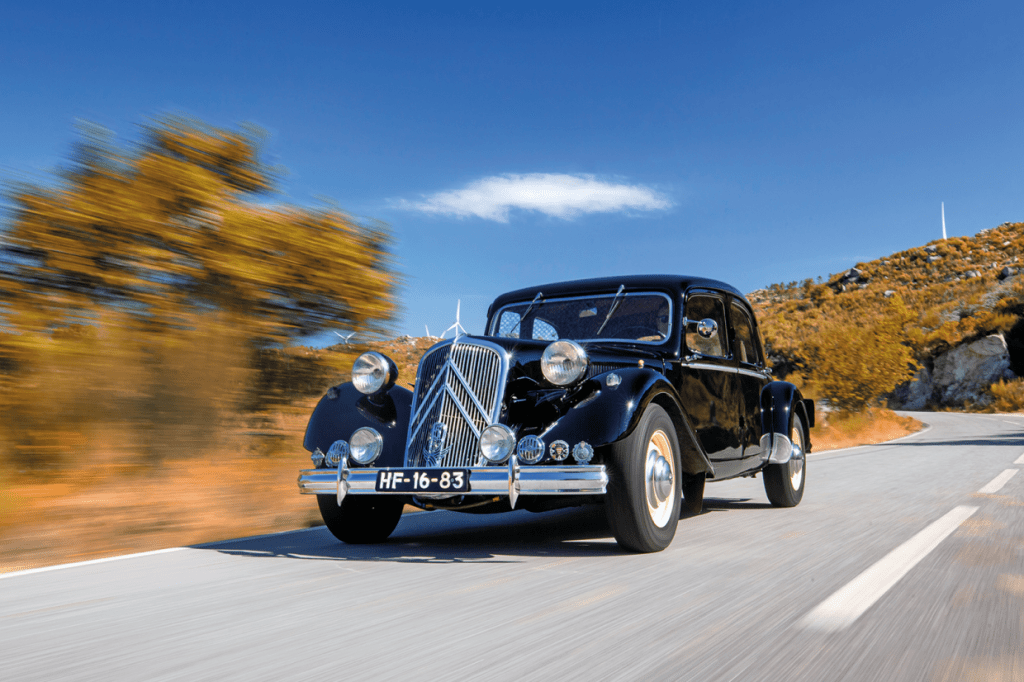

Yet nothing had such an impact on the brand as the introduction, in 1934, of the Traction Avant.

Profound Change

For starters, the Traction Avant was the first Citroën to wear the brand’s iconic chevron-gear branding as a tribute to Mr. Citroën’s successful business activities, something their vehicles have worn ever since.

In terms of innovation, it was the world’s first car to be mass-produced with front-wheel drive (though it’s longitudinal engine-layout never took off), the first with four-wheel independent suspension and the first with a unibody construction, omitting a separate chassis in lieu of the car’s body as the main load-bearing structure.

Its development costs nearly bankrupted the company, and were it not for Michelin, a majority shareholder stepping in to save the marque, they might have simply faded away, like so many other marques.

Thank God they didn’t!

Function vs. Form

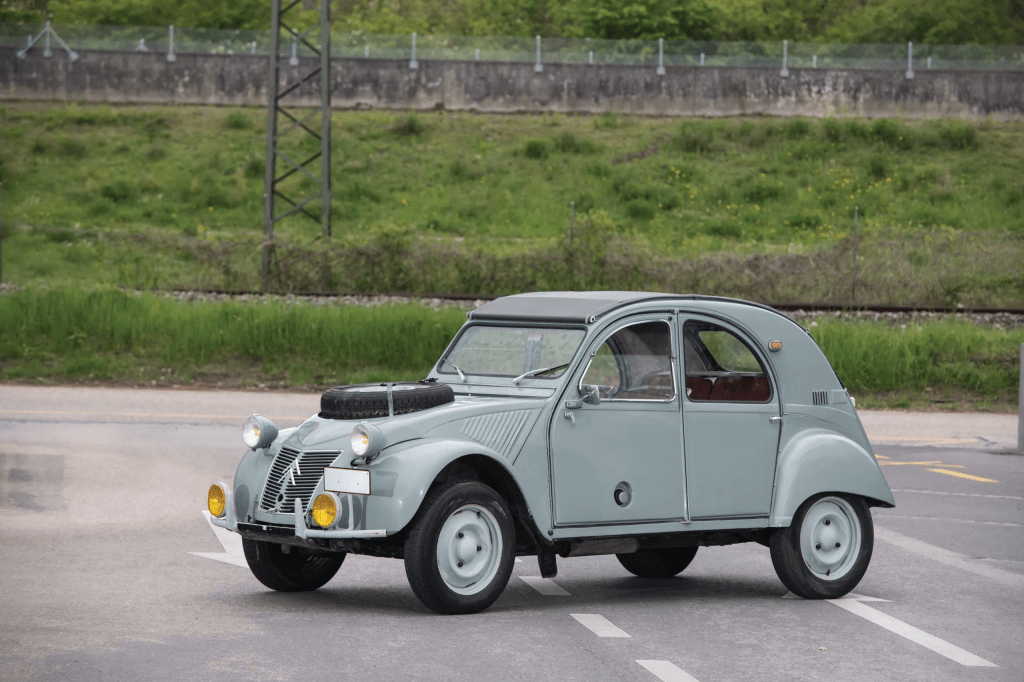

Just before the outbreak of WWII, and having anticipated the need to mobilise the largely rural, agriculturally-employed population of France, they had begun developing something as far from the Traction Avant as… a horse. Or 2 of them.

Having hid the concept from the Nazis, when the war was finally over they dived straight into productionising the design, thus the 2CV was born.

More than just a car, it mobilised the nation of France, giving the near-obliterated country an ability to stand on its own two feet again, to link the country’s large agricultural regions, farms and workers with markets, cities and sources of income. It made the French proud again.

It was everything the Traction Avant wasn’t, yet still as innovative, perhaps even more so. It was ultra lightweight, with just 9hp on tap, but it was incredibly durable, low cost and even cheaper to maintain, was customisable and came with a sliding fabric roof and hinged windows, depending on the model.

It was oddly attractive, an instant cult classic and it showcased Citroën’s ability to recognise product needs and meet them succinctly.

Forget design language or common components, this was Citroën’s mantra.

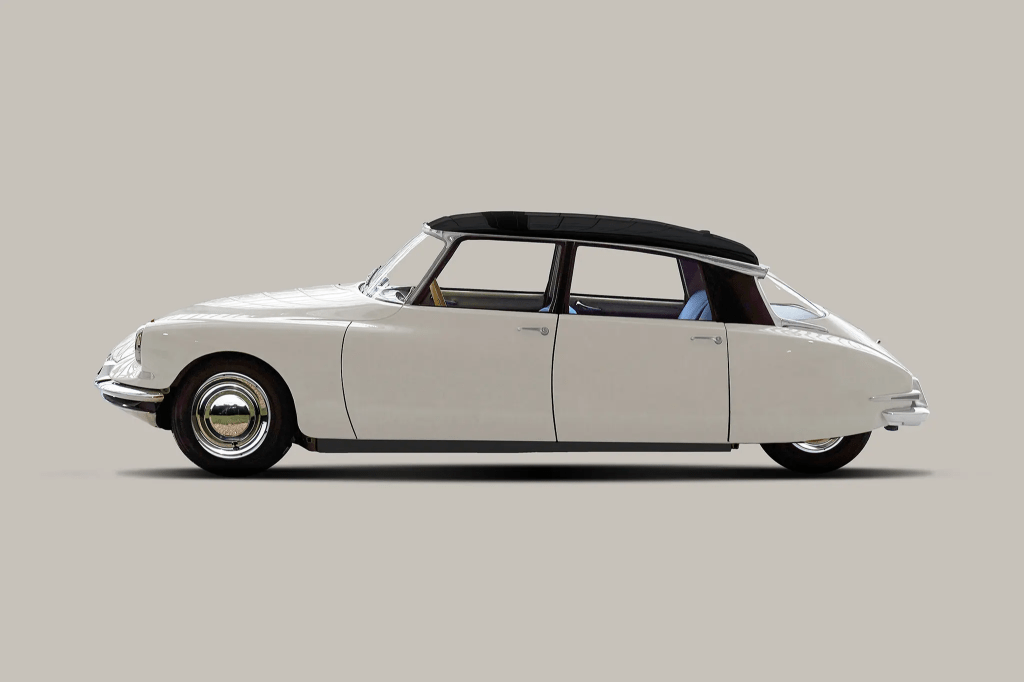

What was next for the brand? Creating the most beautiful car ever made.

Indescribable Beauty, Mechanical Form

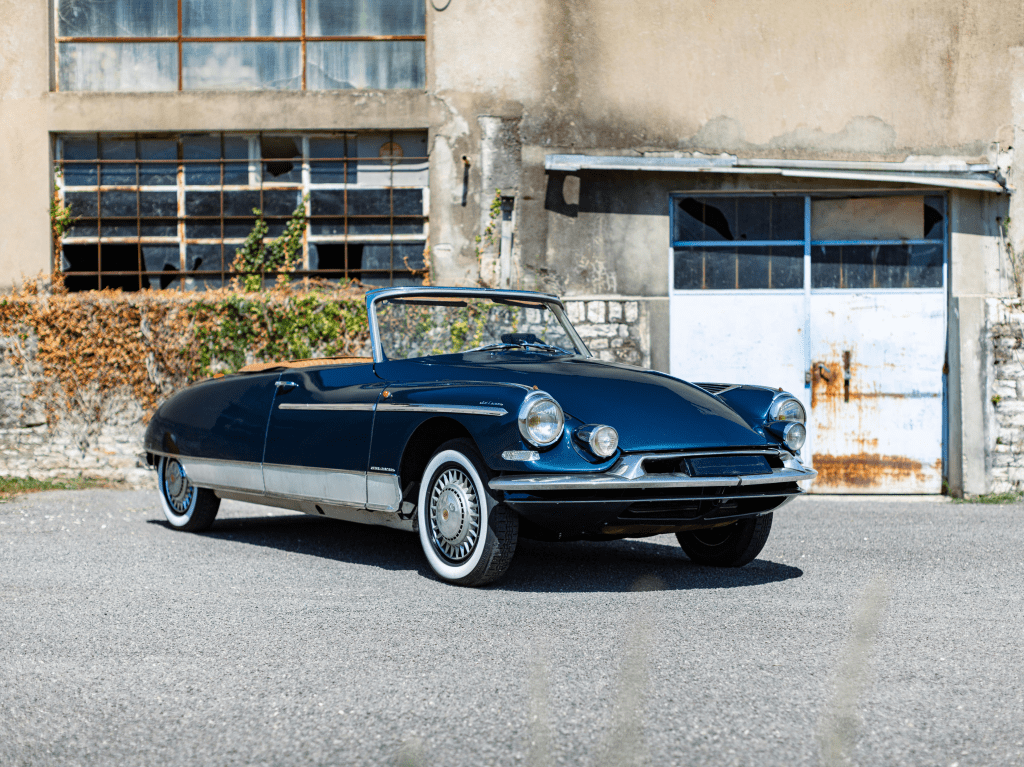

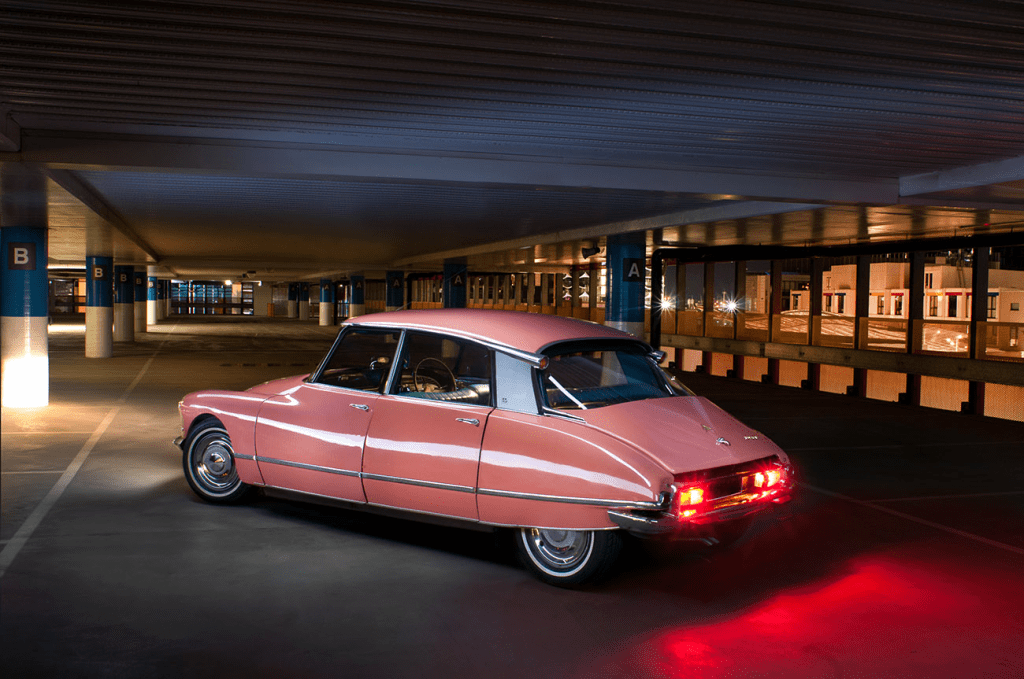

Now before we even touch on technical details, or its history, let me mention a few interesting facts:

It was developed in secret for 18 years, as a successor to the Traction Avant; On its debut at the Paris Motor Show in 1955, it took 743 pre-orders just 15 minutes in, 12,000 during the first day and 80,000 during the show; The single day pre-orders was a record for 60 years, until the Tesla Model 3 smashed it; it’s listed price was equivalent to $28,440 in 2022 dollars.

And now we’re going to talk innovation.

It was the first vehicle to fully deploy Citroën’s patented, and wonderfully novel, hydro-pneumatic, self-levelling suspension system, deemed essential for France’s war-beaten public roads. It was the first mass-produced car with modern disc brakes too, in 1955.

Whilst the suspension offered both automatic self-levelling and driver adjustable ride-height, it also had power steering (the first introduction at such a price point) and a novel semi-automatic gearbox that removed the clutch pedal but still required level-controlled gear changes.

There was a glass-fibre roof to reduce the centre of gravity, different track widths to minimise either over- or understeer and even novel centrelock wheels for rapid wheel removal and re-mount.

This was a car that was as made for driver’s as it was for onlookers.

In fact, as proof of its driving capabilities, the DS achieved multiple major race victories between 1959 and 1974 including the Monte Carlo Rally twice, the 1962 1000 Lakes Rally and the gruelling 1974 London-Sahara-Munich World Cup Rally.

As validation for it’s innovation and design, It placed third in the 1999 Car of the Century poll behind the Ford Model T and BMC Mini, and was named the most beautiful car of all time by Classic & Sports Car magazine, after a poll of legendary designers including Giorgetto Giugiaro, Ian Callum and Paul Bracq.

And in terms of sales success, despite it being a premium vehicle, 1,455,746 examples were sold in total over 20 years, 3 series and a host of model varieties.

It’s brilliance and importance simply cannot be overstated.

Contrasting Fortunes

Even during the lifecycle of the DS, the innovation didn’t stop.

In 1967 they introduced, in several of their models, swiveling headlights that allowed for greater visibility on winding roads. The same year they also established a joint venture with the German marque NSU to develop Wankel engines, which found their way onto certain models but, in essence, failed.

At all model levels, the marque continued to pioneer aerodynamic designs, something we take for granted today, novel suspension systems and innovations that could be financially justifiable in models of all levels, something that simply doesn’t exist currently in the auto industry.

However, this approach also hurt them, leaving gaps in their powertrains (particularly high power ones, limited by French tax laws), an underfunded dealer network outside France and a model lineup with huge gaps.

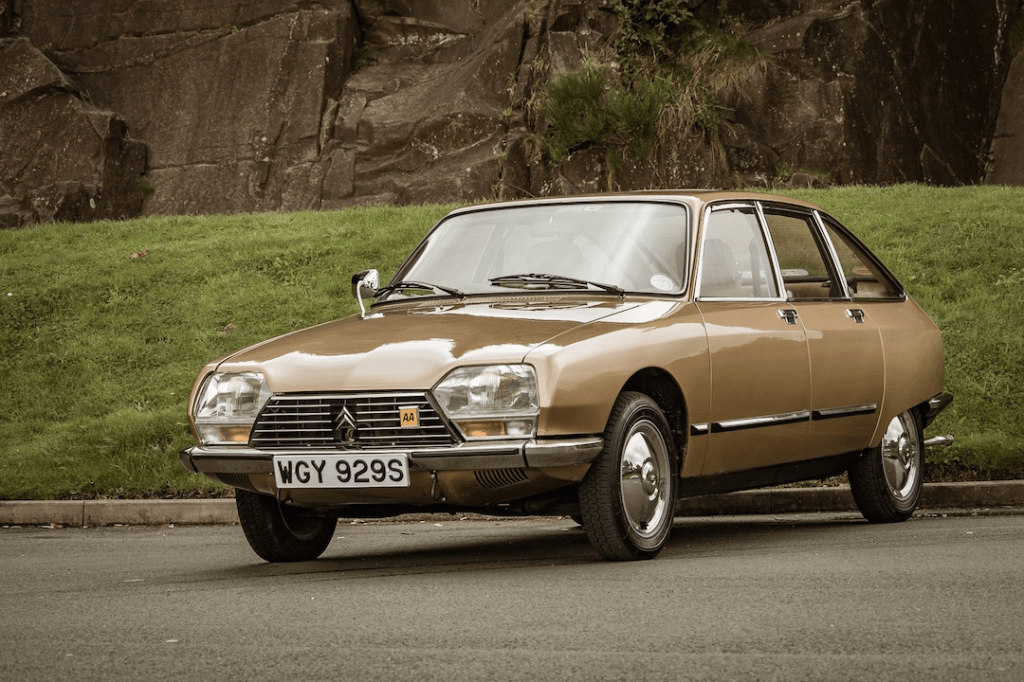

However, after several failed attempts to bridge the gap between the utilitarian 2CV and the beyond-superlatives, premium DS, they eventually launched the GS. Though it didn’t debut any specific innovations, it brought remarkable, existing technology to the C Segment, so VW Golf territory.

Kicking things off with a drag coefficient of just 0.318, which provided the car with market-leading fuel consumption, they added fully independent hydro-pneumatic brakes and self-levelling suspension into the mix, and topped it off with a European Car of the Year award in 1971.

They’d done it again.

In a segment that included the Fiat 128, Ford Escort and Renault 6, the GS was light years ahead, in almost every sense.

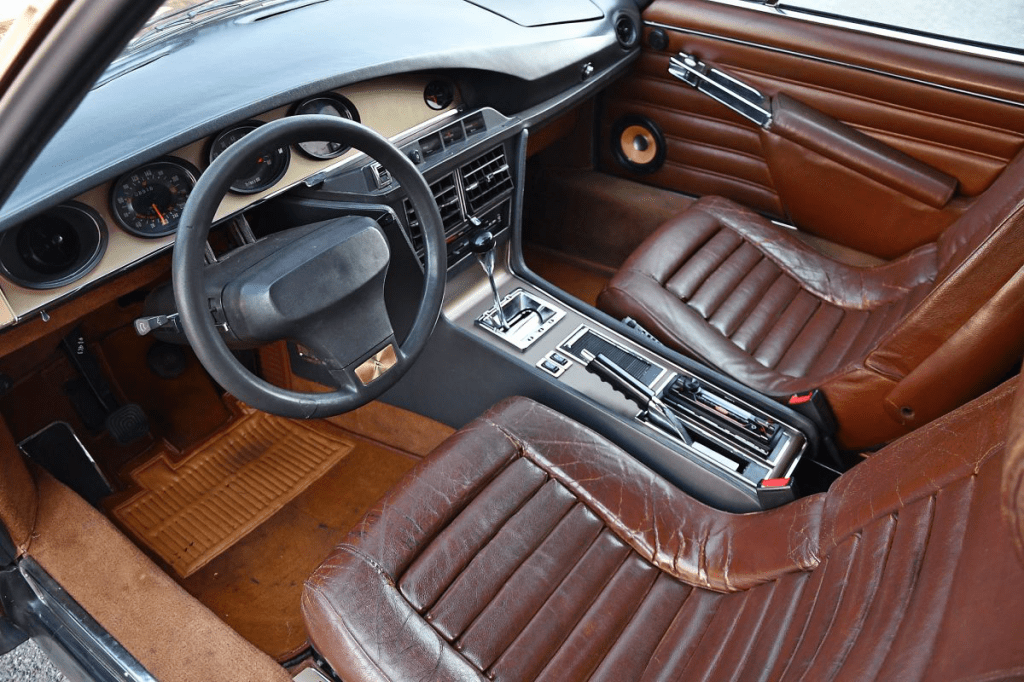

It’s interior featured a dashboard-mounted handbrake lever, with the novel ride-height setting adjuster (for rough vs. smooth roads) positioned next to it and the radio placed between the seats, for improved access. Even the curved dashboard, with clear driver and passenger separation, was novel for the time, and certainly the segment.

They even had a system in place that automatically adjusted brake pressure, without any difference at the pedal, depending on the loads you were carrying. This was a car for families too.

Like any good carmaker, hell product-producer, Citroën continued to evolve the GS with all manner of body styles and trim levels – the 1971 station wagon is particularly charming – until 1979, when they facelifted everything and rebadged it the GSA.

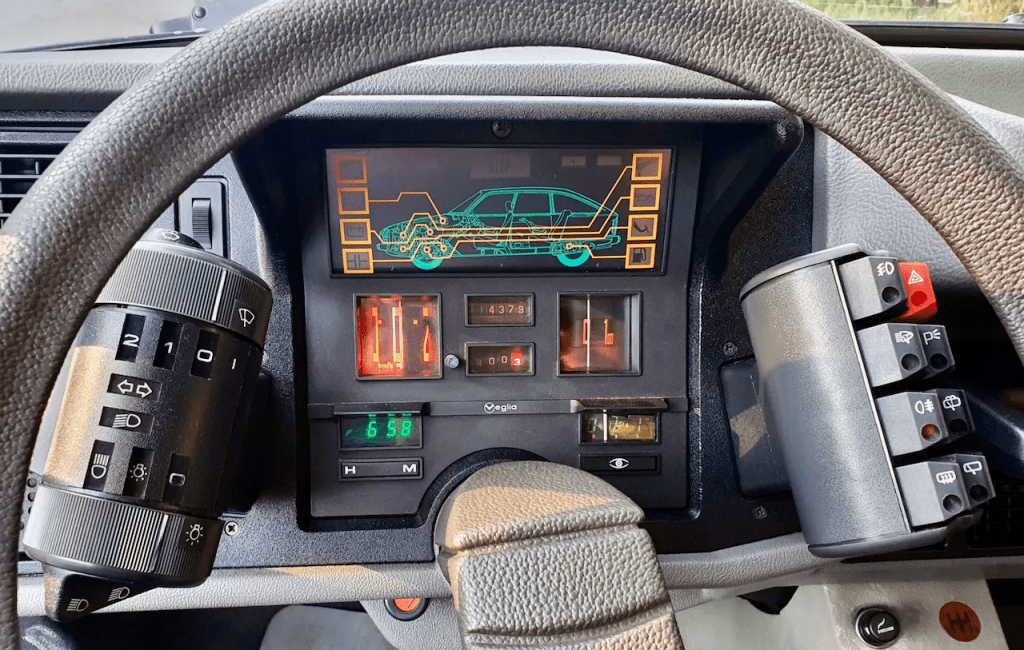

Whilst I wouldn’t normally touch on a facelift, just look at the interior changes!

Something we take for granted now, Citroën were one of the pioneers of mass-produced, steering wheel-mounted switches and levers for improved and safe driver-access. And don’t get me started on the telematics!

Replacing an Icon

So, having conquered the A segment with the 2CV, the wonderful GS a firm competitor in the C segment – roughly 2.5 million vehicles were sold during its lifetime – the next item on their list was a replacement for the majestic DS. This could be no ordinary motorcar.

The French marque had been assessing all manner of underground projects, including a sporting DS variant, a high-powered GT, and various other prototypes, as was Citroën’s habit.

Having been partially-owned for so many years by the pioneering tyre manufacturer Michelin, they had a strong culture of experimentation and prototype testing. It was ok to fail, essentially.

And there were definitely failures along the way, the DS development having almost crippled the firm entirely. They still didn’t have a high-powered engine, so resorted to purchasing Maserati in the hopes of combing the Italian’s powertrains with their own hydro-pneumatic suspension.

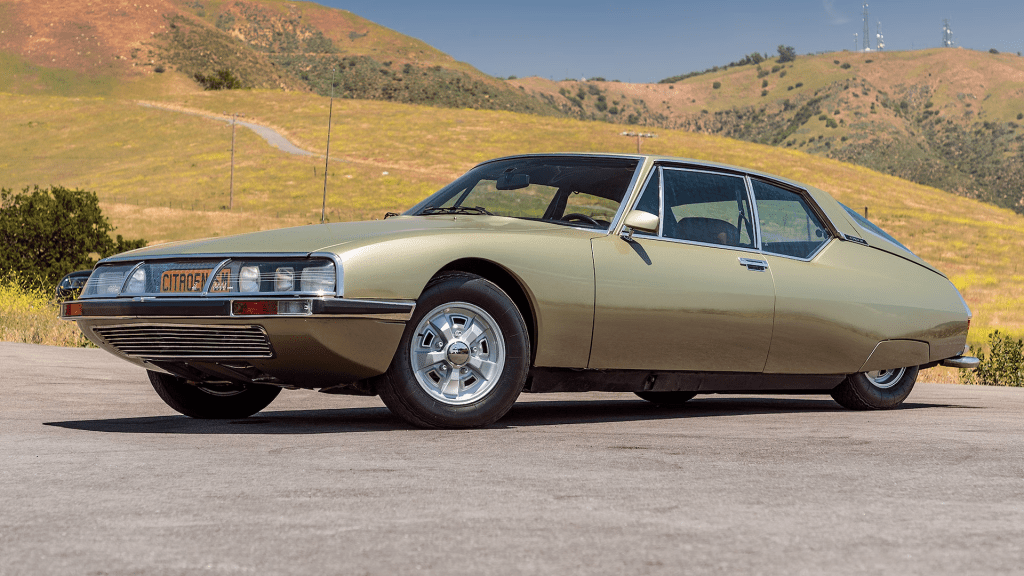

And that’s exactly what they did with the SM.

With just a 2.7l V6 on tap, and up against GTs from the likes of Jaguar, Ferrari, Alfa Romeo, Porsche and Mercedes-Benz, it should have flopped. And there’s an argument to say it did. Though that’s a little short-sighted.

For starters, its elegant, sleek design gave it best in class fuel economy, a critical factor for a GT, a vehicle in which you hope to rack-up considerable miles. It’s combination of a Maserati-designed powertrain and its world class suspension generated rave reviews for its dynamic ride and handling, again something crucial for a GT. It was peerless in this regard.

Its stopping distance was the shortest of any vehicle that Popular Science magazine had tested. And in 1972, Motorsport magazine emphasised the “rare quality of being a nice car to be in at any speed, from stationary to maximum.”

With the exception of uncompetitive acceleration for its class, this was a brilliant GT by all measures. And we haven’t even touched on the innovations yet.

They pioneered a power-assisted steering system, called DIRAVI, that provided significant assistance while parking, but almost none at motorway speeds, to avoid the sensation of “light” steering when cruising. The system adjusted the hydraulic pressure on the steering-centreing cam according to vehicle speed, so that the amount of steering feel remained almost constant at any speed.

There was the usual additions of the marvellous steer-guided headlamps and hydro-pneumatic suspension, whilst the SM was the only front wheel-driven car in its class. The wiper-mechanism automatically varied its speed to accommodate changes in rain ferocity at low speeds, whilst even the wheels were novel, the SM debuting factory-fitted fibreglass wheels for off-road racing to reduce unsprung mass.

The SM is not often talked about, perhaps in part because it only had a 5 year product life, and just 12,290 were ever sold. it’s also been linked to Citroën’s bankruptcy in 1974, a significant moment that led, in my opinion, to the death of the marque’s innovative culture.

Demise

So what happened?

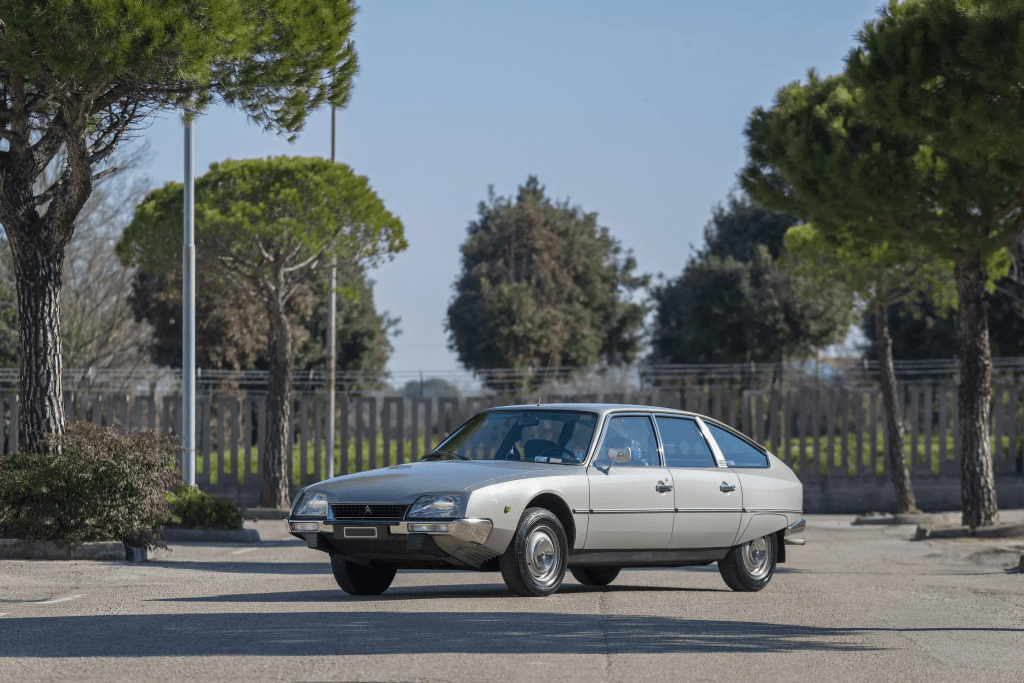

Well the marque, having been through not one but two bankruptcies (Traction Avant and DS), still launched the CX, it’s true DS replacement in the E segment executive car category, to rave reviews, the car winning European Car of the Year in 1975.xm

But with some of Citroën’s innovations outlawed by US regulation, the world suffering an oil crisis and the marque still stumbling through bankruptcy, it was evident that their approach to innovation was over.

Following government intervention, they combined with Peugeot between 1974 & 1976 to eventually form PSA Group.

And in the subsequent years trundled through average car after average car.

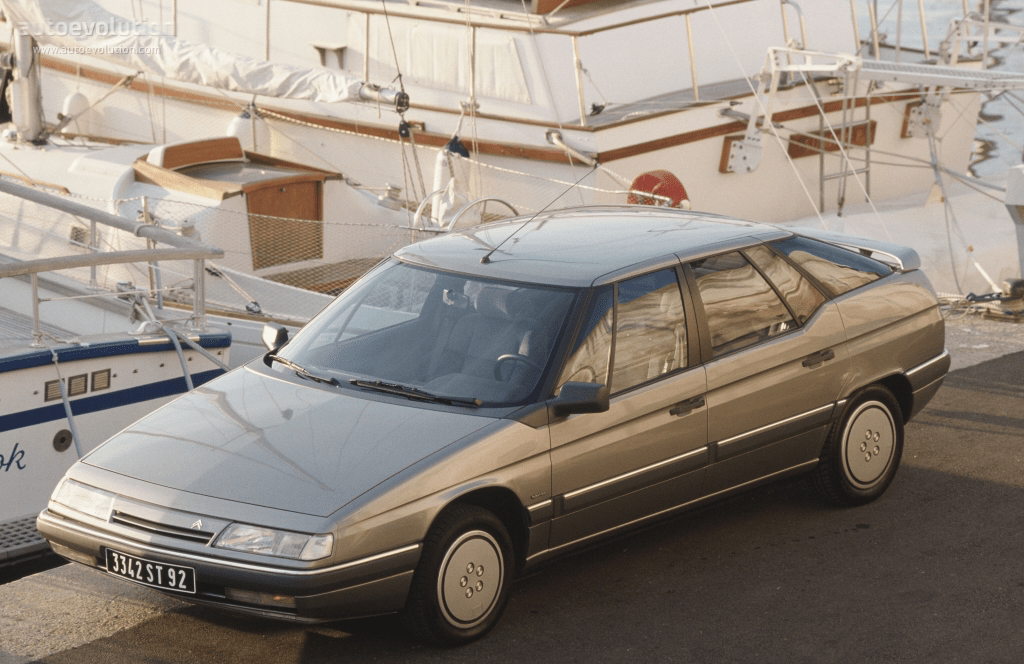

Though the CX’s replacement, the XM, also won the European Car of the Year award in 1990, the firm’s last win, the ’90s and noughts oversaw all manner of sludge churned out, although there were many marques globally that followed suit.

Shifting into the present, the DS is now represented by its own brand, though still within the PSA stable, and it’s failed to capture anything of the original vehicle’s innovation or design excellence.

And perhaps therein lies the problem. When Citroën pushed the boundaries, they created such excellence as to set themselves up for failure when attempting to repeat.

Which makes what happened next so tantalisingly frustrating

False Promise

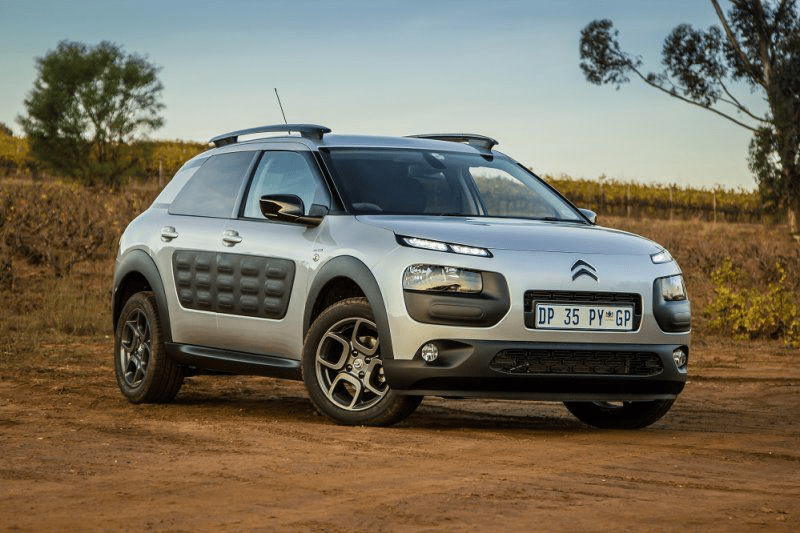

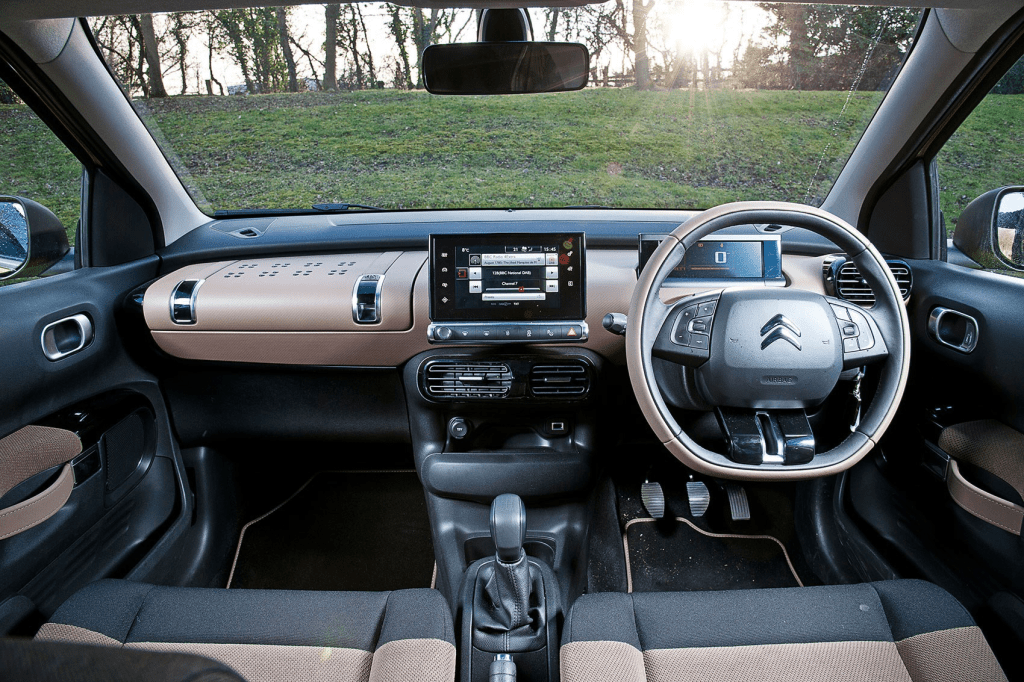

In 2015, the French marque launched the C4 Cactus, a quirky crossover SUV with almost no competitors. With such technology as its patented air bumps, header-mounted passenger airbag and novel dashboard, had Citroën done it again?

Actually, yes they had.

Receiving rave reviews for it’s unique approach to an SUV, specifically the bright, roomy and airy cabin, it’s low cost of ownership and its technology-limited dashboard, it appears that the French marque had once again really listened to the voice of the customer, had developed novel technology to meet these demands and had created a new segment simultaneously.

Others would subsequently join the bandwagon, but not before several publications would award it “World Car Design of the Year” and “Production Car of the Year”. It placed 2nd in the European Car of the Year competition in 2015.

But just 2 years later, for the model year 2018, Citroën made a host of changes to the car and dialled back many of the quirks, charms and decisions that had made the vehicle so unique, so pioneering.

It was clear that the marque were happy to remain a producer of Russian Doll-esque products with no distinction and a severe lack of innovation.

Though there’s an argument that the entire industry suffers from this affliction, allowing newcomers like Tesla, with an alternative approach, to affect such a dramatic change, when innovation is in your DNA, it’s inexcusable.

I grew up a lover of the Citroënesque approach to cars, particularly my uncle’s CX and the magic of that hydro-pneumatic suspension. As an adult, however, I appreciate the innovation not as magic but as lifestyle-enabling and genuinely useful.

What I’ve witnessed in the interim years is a marque ignoring their legacy, and just as Citroën has to so many of their own innovations, I’m turning my back on them.

It’s gonna take something remarkable to make me turn around again.

But don’t worry, I’m not holding my breath.

***

We don’t often do this at CLT, share our honest opinions on the state of the industry, or delve into our feelings on particular marques and models.

So let us know your thoughts in the comments section.

And be sure to subscribe below to avoid missing out on future articles. Don’t worry, they won’t all be this biased!

Leave a comment